Labyrint

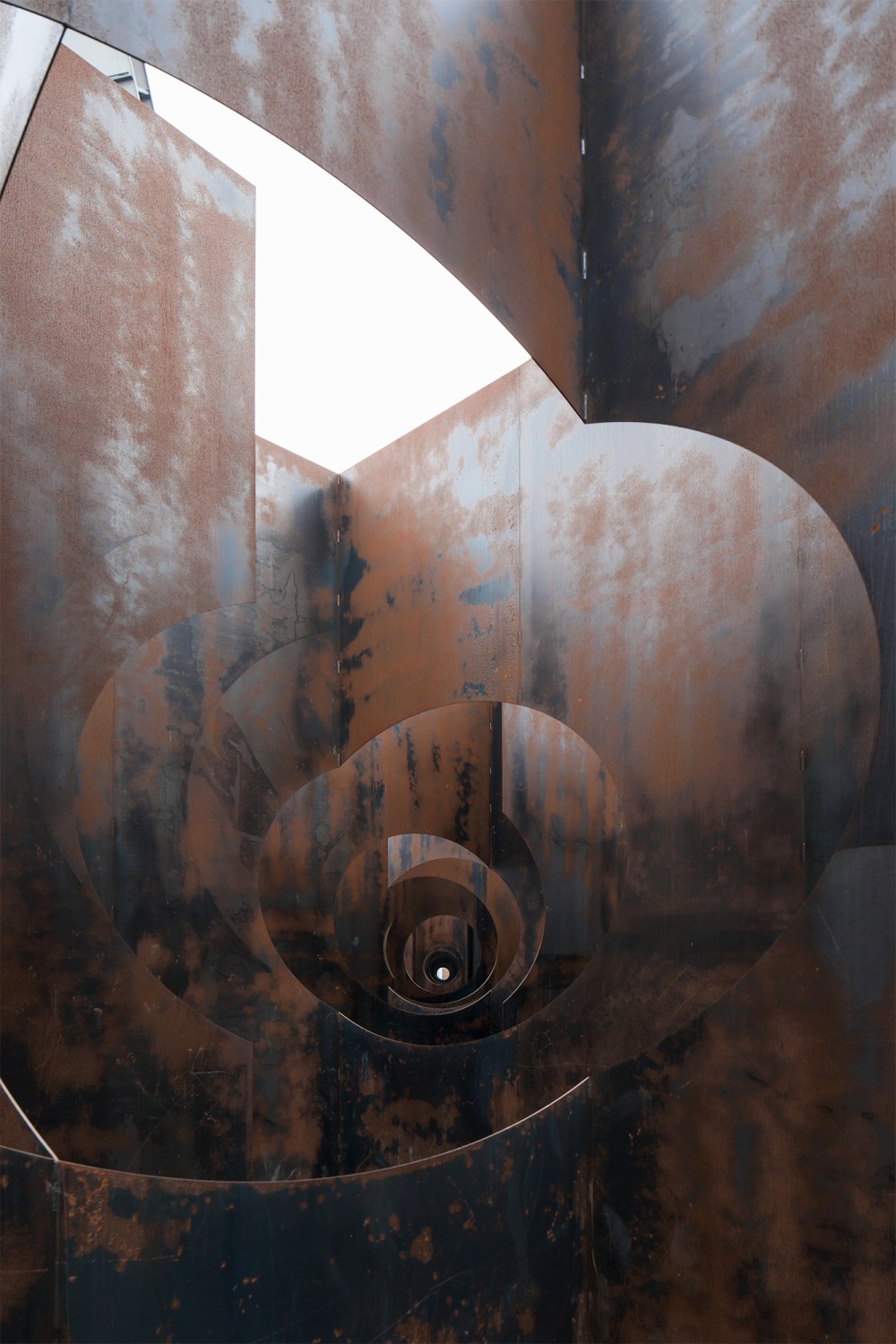

A large-scale steel maze, as a reprise of the ancient typology of the labyrinth, is set up on the main square of the C-mine cultural centre in Genk. In the grand tradition of the mythical first architect, Daedalus, the labyrinth is first and foremost a place of imprisonment. Contrary to the ancient quality of the labyrinth, characterised by its impenetrable and disorienting set of walls, the installation in C-mine is punctured by geometric voids: big cut-outs in the walls, reminiscent of the work of Gordon-Matta Clark, create internal spaces in the areas where they intersect. At several points, the openings allow the visitors to get a grasp on where they are and orient themselves. The openings subvert the essence of the labyrinth: they counteract the sense of imprisonment with views and open spaces in which visitors can wander and encounter each other.

Moreover, visitors can ascend the mine headframe and view the labyrinth from above. From this viewpoint, the floorplan of the labyrinth becomes readable at one glance, heightening its object-like appearance on the square. The maze is not aligned with the square but rotated 45 degrees relative to it, affirming its autonomous character as an (architectural) object, while also articulating the square through smaller subspaces.

Because of its minimal structure and joints, the work reads almost like a mathematical model, as its planes and the volume that circumscribes it are brought to the fore. The openings, then, become readable as negative volumes, removed from the labyrinth. The labyrinthine walls, more specifically, can be interpreted as the framework to showcase the labyrinth’s voids.

COMMISSION

C-Mine

DATE

2015 (permanent)

LOCATION

C-mine square, Genk (BE)